In hindsight, it must have been the hat or the wifebeater, because about five minutes into my visit to the ‘Grand Opening’ of Fiume—the “art gallery for a new regime”—I was being recruited to join a white supremacist group chat. The hat was standard camo with the words ‘Ragin Cajun’ written in orange on the front. The guys were wearing blue blazers and t-shirts and talking about their group chat on Telegram where they were ‘getting organized.’ “We saw you from across the room and thought, that guy looks like one of us,” he said. “You know, the next generation of white boys.” He asked me to add him on Instagram, with the caveat that “I only post normal shit there.” As I turned my head, I noticed one of the blazer boys spreading his lapels to reveal a Nazi insignia on the breast. He closed his eyes and sucked on his lip, like a racist Hulk turning himself green.

I’m not sure exactly what I was expecting, heading to an art exhibit billed as the “Theatre of Cruelty.” But hanging out with Neo-Nazi’s was not on my radar. Perhaps that was naive, given the “Dictator Pageant” promised on the program. But for all my wandering through Far Right spaces, I’d never encountered true, straight-to-the-vein fascists first-hand. I was used to the performative fascists: the Dimes Square edgelords with five-bedroom apartments on the Upper West Side. The ones that said ‘retard’ and called it avante-garde. I suppose I should’ve known something was different here: that their call for “aesthetic rebirth” was more like a dog whistle for, well, dogs. But you can never really know with these things—after all, the gallery was in Chelsea! Wasn’t the “funeral for irony” supposed to be ironic?

I showed up thirty minutes late, hoping to snag a free ticket by calling myself press. Turns out that this was not the best strategy and I spent twenty minutes hanging by the door. Clearly unsure about what he’d signed up for, the bouncer asked me nervously what was going on in the room upstairs. I told him it was a fascist art exhibit for the New Right, and he bulged his eyes and sighed. “I never would have agreed to work the event if I’d known.” A couple minutes later, one of the organizers came down and said that I’d gotten approval from the ‘higher ups.’ The man in the white pants, who I recognized as Nic Dolinger from Sovereign House, looked me straight in the eye and said, “Please don’t fuck me.” I smiled and nodded my head, walking into the industrial elevator. It opened like a mouth from floor to ceiling with wooden double doors. I was standing next to an elderly man with a large misshapen hump on his back.

The room was long, rectangular, and white. At the front of the room, a couple desks were set up where the organizers were standing. In the middle, there was a table with some water and wine. Behind that, a divider was blocking the entrance to the room next door, where I reasoned the art was hanging. About thirty people were waiting around for the event to start—a group I’d describe generously as ‘eclectic.’ What I mean by this is that pressed amid your standard art-faring white people in maxi skirts and vintage french workwear, there was a prevalent theme of eighties-style goths and punks. One guy had an eye patch and a concave chest like a recovering throat cancer patient. The photographer had a shiny bald head with one eyebrow missing. Metal spikes protruded from leather jackets like Rhinoceros horns. The blue suit boys were huddled as a pack in the corner.

The first shock was the sight of a large, hand-drawn swastika inlaid with Stars of David and the words, “Pray for Irony’s Sake.” It was draped off the back of a bald waifish girl in a pencil dress who was wearing a black and yellow flag as a cape. I realized later it was the flag of anarcho-capitalism, which was (kinda) fitting for the event, named as it was after the Free State of Fiume—a small, port-city in present day Croatia that, in 1919, was the site of an Italian fascist insurrection.

The short version of the Fiume saga (at least the modern one that the art gallery was referencing) is that, following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire at the end of the First World War, there was a hostile dispute among the Great Powers over who should take over what is now Rijeka (née Fiume), a port city at the mouth of the Adriatic. Most of the people that lived there spoke Italian, with minorities of Croats and Hungarians. But the Kingdom of Yugoslavia1 thought it should belong to them, and so did the Kingdom of Italy, who tried to force this agreement into the Treaty of Versailles. The Slavs wouldn’t have it, so instead, American President Woodrow Wilson suggested that Fiume should become an independent buffer state, and home to the League of Nations. This worked for about five minutes, and soon the territory descended into political chaos, changing hands between the Slavs, the Italians, the British and the French, multiple times. And that’s when a group of 186 “legionnaires,” led by an Italian poet and aristocrat named Gabriele D’Annunzio marched into the city and proclaimed Fiume an Italian outpost. With 2,500 troops defected from the Italian army, D’Annunzio held the city for fifteen months and installed himself as ‘dictator.’

While the episode is dramatic for obvious reasons—a ragtag team of “legionnaires” take on the imperial powers and win—the story has lived on as a central node in the fascist imaginary for a couple of reasons. One is that Vladimir Lenin supposedly sent D'Annunzio a box of caviar. Cool! Another is that, while D’Annunzio was the reigning chief, Fiume became a nucleus for radicals and artists from all over Europe. But the main reason that Fiume is remembered with such fanfare is that it quickly became a blueprint for the nascent Italian Futurist movement. Which became the foundation for the nascent Italian Fascist movement. And the guy who laid the groundwork for both of these ideas—writing some of its core texts from a bunker in D’Annunzio’s proto-fascist city—was none other than Filippo Tommasso Marinetti: who you might think of as Mussolini’s right hand man.

Back in Chelsea, the gallerists were attempting to transfuse these symbols into vibes. The event started with a ritual cleansing exercise, bashing the idols of the old regime—which, in practice, meant destroying two glass poster frames seemingly purchased at Target, ripping up a program from another gallery, then sweeping up the glass and paper and tossing it in a bin. A guy in a cowboy shirt went on about the cucked literati, the carcass of civilization, the arsonists of contemporary art, the gods of the old regime, etc. We were sentencing to death the remnants of modern art and the false idol of prestige. “The vanguard doesn’t wait for the plebs,” he said. Then asked: “What is it to be sincere in a meaningless world?” A worthy question, whose answer I was very much looking forward to. Turns out the answer was a dance party for a couple of girls pretending to be ‘dictators,’ dressed in revealing outfits of coquette-core. If I’d known, I would’ve just gone to the Brooklyn Center for Theatre Research.

Now if I’m making this seem stupid and banal, that’s because it was. After a short recitation of what I’d call ‘social malady poetry,’ each ‘dictator’ took their turn strutting the enclosure, offering their own string of declarative statements wrapped in boring and cliche’d abstractions. It was all Nietzsche’s will to power this, the harnessing of machines that, the necessity of the absurd, the failure of the liberal regime, etc. At one point, Nic Dolinger got on the mic and asked the crowd to take a moment of silence for the destruction of the American republic. Apparently Trump wasn’t radical enough? One of the girls started reading a speech I could’ve sworn was Augusto Pinochet, the Chilean dictator. I got a text from A. asking if they were playing Kanye’s new song, Heil Hitler.

Amid a passage of prose that was particularly baroque and vapid, a guy in a muscle tee that said ‘FREEDOM JIU JITSU,’ started heckling one of the performers, who was dressed up like a demonic Ursula with costume feathers, colored contacts and a hooked prosthetic nail. She stared at him and grit her teeth like a manic vampire, clearly unsure what to do. He started beaming her with criticism like, “That’s not even right wing. What are you, a lib?”

There were a number of Black people in the room and I wondered how they ended up there. I spoke to one of the poets, who was Black, and asked her how she got involved. But instead of speaking openly, she looked away from me and demurred. Apparently one of the organizers had seen a clip of her poetry on Instagram. She didn’t want to say more.

All of this is to say that the crowd was far more interesting than the performance. I kept asking people how they heard about the event and the answer was some combination of Twitter and knowing one of the performers. People were kind of cagey about their real names. Most people told me they were anons. “I used to be a face faggot,” one person said, “but then I switched.” Meanwhile, the cameras flashed endlessly, with a particular affinity for the crowd, and I wondered if they were hired by the Feds as research into white nationalism in New York City.

People kept on telling me about new Far Right groups that were popping up. Apparently, a month earlier, there was a meeting on the Upper West Side among two groups that wanted to charter a new right-wing society. One was filled with gay Koreans and the other was filled with Jews, but they couldn’t agree on how to position Nazi memorabilia. The gay Koreans wanted more; the Jews wanted less. So they remained split. Thank god I didn’t wear my Star of David necklace, I thought to myself. I was seriously considering it before I left the house.

There were a lot of Jew slurs! There were a lot of slurs in general, but Jews received a disproportionate amount of attention. As the performances waned, I found myself talking with a tall dude in a blazer who revealed that he was Paul Bandera, the grandson of Stepan Bandera—the leader of the radical Ukrainian nationalist movement from 1940 to 1959, when he was assassinated by the KGB. Hailed by many Ukrainians as a kind of liberation martyr, Bandera is controversial because he allied with the Nazi’s during World War Two and organized pogroms against both Jewish and Polish civilians. I told Paul that I was Jewish and asked him why there seemed to be so much enmity for Jews in the room. He argued it had something to do with the role that Jews played as state-intermediaries in medieval European history and how that translated to contemporary New York. You have to understand that for most of Ukrainian history, he said, when the average citizen interfaced with the state—be it in the form of tax collection or lending—the face of that interaction was the Jew, who systematically exploited them and held them down as a kind of under-class. I countered that Jews were held in that position because they couldn’t own property, and could be expelled at any time. So cozying up to the state was a form of self-defense. We agreed it was complicated and then broke off to look at the art. But I still didn’t feel that I got the answer I was looking for.

The heckler was right about the art. Inspired as it might have been by Italian Futurism, the result was a cliched mess of CGI romanticism, complaining about the tyranny of social media and conformity, invoking folklorish images of quotidian life in the provinces. There was a series of nudes that looked like they were painted by an undergrad at the New School. A series of collages with garish scenes from a fallen world overlaid with American film-noir. Everything was going for eye popping prices, as if nothing was really for sale. Most of the art looked like sad-girl nihilism that you might have found on Tumblr circa 2006. Some of it (perhaps intentionally?) was really gay—like, if Caspar David Friedrich was inspired by Bronze Age Pervert.

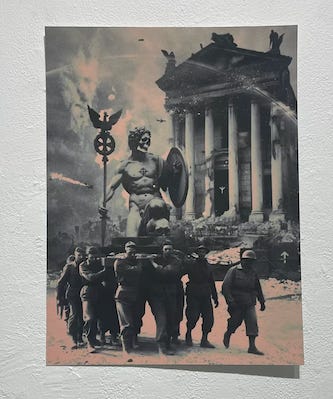

The one piece that did sell was by far the most provocative. A kind of Apollonian Übermensch with a trident of the German coat of arms sits upon a platform held by a crew of distraught soldiers on a march. In the background, war planes fall from the sky over a tall Hellenic temple amid a pile of rubble. Inside the mouth of the temple you can see a symbol. I searched for it on Google. It’s the rune of Algiz, a letter from the runic alphabet that was used as a symbol of vitality among early Aryan folk religions. The original meaning is ‘elk.’ It was also used by the Nazi’s as the symbol for their lebensborn program—eugenics for “racially pure” Aryan children. The piece was purchased by one of the dudes in the blue suits. Nobody was surprised.

As the crowd started to thin, the gossip started, and people started ripping into the dopiness and incoherence of what they’d seen. The whole presentation felt like a high school talent show, someone said, but with less preparation. Apparently, the models from the dictator pageant had been hired that day. The art had been hung an hour before people arrived. “Where was the Italian Futurism?” asked the one friend I recognized there, who I’ll keep anonymous so as not to place him at the event. At least in the beginning, he said, people like Marinetti had real style—they had demands, strategies, specific complaints about the ways technology was being harnessed. None of that was here. It was as if they assumed that trading on the shock factor of fascism was justification enough. “They’re doing real fascists an injustice,” someone said with a wink. But they were right.

That’s when Rachel Haywire, the event’s main organizer, started floating around the room, taking offers of congratulation with three fingers like she’d just finished a ballet. She was dressed in a purple-pink tube top with a forest green midi skirt and tall leather boots. Probably one of five people wearing color in the entire room. I don’t know Rachel but I’d started following her on Twitter once she became a lolcow in one of my group-chats, her tweets shared for their ingenious combination of absurdity and grift. So in an attempt to understand what was really going on, I read what you might call her ‘origin story.’ Which, perhaps unsurprisingly, starts at the post-game of Burning Man.

It’s 2004 and a group of guerrilla performers called the Cacophony Society are heading to Santa Cruz to crash a reading of Chuck Palahniuk’s new book, Choke. Our heroine is dressed in military-industrial drag and she’s tired of her Yuppie occult polycule, so she ditches the reading and meets a man named Rob the Übermensch outside. “Kill the weak,” he says, without irony. “Exterminate the human race.” She’s attracted to his sincerity—the way he quotes Nietzsche resonates. So they become enmeshed and romantic. They call themselves “fashbies" because they’re “fascist aspies.” They talk about exterminating neurotypicals and queering Darwinism. They drift through San Francisco. They fall in love. Until she wakes up in Rob’s apartment with the walls covered in blood. Convinced he was the leader of some alien Nazi cult, he’d cut himself and was drawing sigils. So she leaves. She blinks and it’s twenty years later. It’s 2024 and she’s at Sovereign House for a Curtis Yarvin poetry reading. The eternal recurrence had completed its cycle and now she’s being reborn. She thinks of all the Rachel Haywire’s she’s been, and all the Rachel Haywire’s she will be: “the beginning and the end of my life.”

Now it’s a year later. Enter Fiume.

Thinking about it, I guess that’s why she wasn’t bothered by the gallery books with titles like “BLOOD SOIL PAINT.” Compared to a morning of bloody sigil production, what’s so scary about some light New York fascism? As I was flipping through a book called the “The Cultured Thug Handbook,” Nic Dolinger came over to the group and started complaining: “I’m sick and tired of being a cringe-shield for these people,” he said. “Honestly, I’m done. I’m going to quit.” I thought to myself: I’m surprised he’s being paid. The group tried to calm him, while he wailed about how difficult it’s been. “Bro, you have to promise me that all the conversations you heard here were off record.” I smiled and nodded politely.

With the room near-empty, one of the guys said matter-of-factly that the older man with the humpback was a walk-in off the street. “Apparently, he just likes Chelsea art galleries,” he said, “and comes to random events.” Everyone in the group laughed and I dashed away to find him, hoping to ask him about his experience. But he was gone. I walked through the double doors and back onto the street. I felt a strange craving for chicken soup.

It was called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes at the time. Later, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

💯

Very funny (and unnerving). Captures the utter incoherence of our moment.